founding the school?

were doing; he didn't think it was a good idea. He lost a son and a

daughter, and now his son was building a school for orphans. You

had other people who thought, "Well this could be a good idea, but

why is he doing what he's doing?" There are misconceptions that in

order to change people's lives you need to be rich and connected;

they thought that maybe I wanted to be a politician in order to do

this. Also, people have a misconception about Africa. They think

nothing in Africa works. They read stories about corruption, and

they think nothing going to Africa is going to work. Many people

here who were potential donors were doubting whether it would

work. But we had a holistic view. There was micro-financing, we

had a library. Many people including some of our board members

said to me, "Can we maintain all these programs?" We listen to

the people on the ground first and foremost, more than the donors.

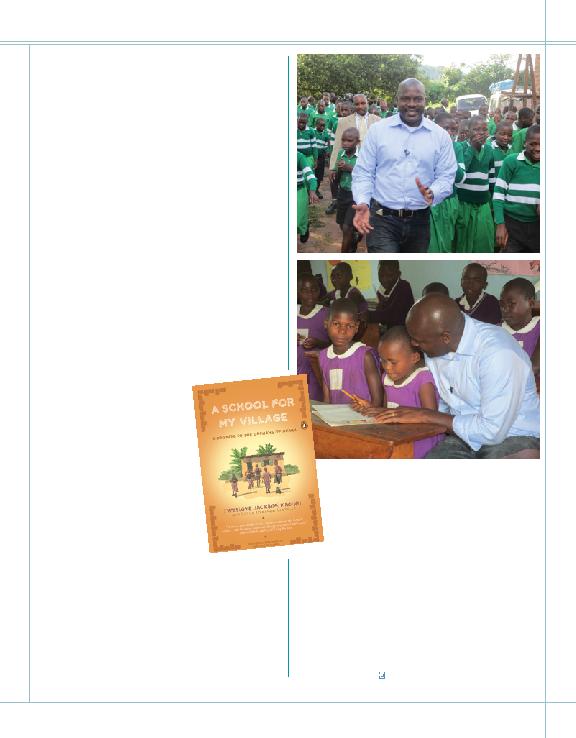

Instead of using a picture of a child to draw sympathy, we use a

positive story about a child on the website. It's a different way of

doing things, the way we've presented people. We want you to be

involved because you believe in the child and you want to make

a difference to the child not because you are thinking "Poor

African child." Yes, you can do things differently. You can give

people dignity and respect them while still making a difference.

Nyaka Project?

school. Our children have finished primary

school; we proved we can do what no

one has done. That's because we used

a holistic approach. We made sure that

adolescents attend school through puberty

because they get sanitary products. When

my sister hit puberty, she dropped out of

school because she could not walk seven

miles with leaves as sanitary products.

We've provided sanitary products, clean

water, two meals, healthcare, a library that holistic approach has

helped them. Our children have passed their exams 100%! We

expect they will pass again in November. I was invited to address

the United Nations because the United Nations was failing on this.

They are looking at education alone without looking at the other

factors. We want to have our own system that will encourage

the holistic approach teachers who teach, care, and give clean

water so these students will be ready to go to university.

play soccer two times a week when I'm in town--I try

on many swimming training practices. We travel a lot, whether

we're traveling for work or just for pleasure. We just came from a

vacation in Puerto Rico. In the beginning, it was not so balanced.

For nine years, I had a full-time job at Michigan State University

while also running the project for some time. So in every moment

of free time, I would work on the project. Now I take vacations.

When anybody's beginning to do the work we're doing, it's going

to be hard to have balance, but without being sane and in good

health, it will be hard.