22

GUNAIKEIA

VOL 18 N°7

2013

Dernier point, «

à prendre cependant avec précaution car il

ne s'agissait pas d'une étude randomisée», précise Rosen-

thal, la survie a été de 91,9 mois lorsque le diagnostic a été

effectué moins d'un an après le dernier dépistage contre

48,8 mois lorsque le diagnostic a été réalisé plus d'un an

après le dernier dépistage (p = 0,037).

Cancer de l'endomètre: une sentinelle du

syndrome de Lynch

«

Le syndrome de Lynch est une susceptibilité héréditaire

de développer un cancer du côlon et un cancer de l'endo-

mètre, de l'ovaire, de l'estomac, de l'intestin grêle, du foie,

de l'appareil urinaire supérieur, du cerveau et de la peau»,

rappelle Sarah Ferguson (toronto). Pour le cancer de l'en-

domètre, ce risque est de 30-60%, alors qu'il n'est «que»

de 2% dans la population générale. il est par ailleurs sou-

vent un cancer «sentinelle» de ce syndrome et justifie donc

à ce titre un dépistage spécifique de manière à pouvoir

anticiper un second cancer et en diminuer l'impact (26).

Reste à savoir quelle est la meilleure stratégie de dépis-

tage, ce que l'équipe de Toronto a investigué de manière

prospective sur tous les cancers endométriaux histolo-

giquement confirmés dans son centre (n = 118) et dont

un grand nombre avait une histoire familiale suspecte

(n = 25) (27). Une recherche génétique a été effectuée,

couplée d'une part à une analyse biologique de la tumeur,

d'autre part à une analyse des caractéristiques propres au

cancer de l'endomètre du syndrome de Lynch (infiltration

lymphocytaire tumorale et péritumorale, hétérogénéité de

la tumeur, situation préférentielle dans le segment infé-

rieur, différenciation mucineuse). Ce travail a conduit à

suspecter un syndrome de Lynch dans 17% des cas et à

établir, d'une part, que l'histoire familiale n'est pas suffi-

samment discriminante et, d'autre part, que la morpho-

logie du cancer ne permet pas de stratégie efficace de

dépistage, contrairement à l'immunohistochimie. Et ce

«

particulièrement chez les femmes de moins de 60 ans, un

examen à réaliser chez toutes les femmes dont l'histoire

familiale est simplement suspecte», conclut-elle.

Références

1.

Kehoe S, Hook J, Nankivell M, et al. Chemotherapy or upfront surgery for newly

diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer: Results from the MRC CHORUS trial. ASCO 2013.

Abstract#5500.

2.

Rose PG, Brady MF. EORTC 55971: does it apply to all patients with advanced state

ovarian cancer? Gynecol Oncol 2011;120(2):300-1.

3.

Katsumata N, Yasuda M, Takahashi F, et al. Dose-dense paclitaxel once a week in

combination with carboplatin every 3 weeks for advanced ovarian cancer: a phase 3,

open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2009;374(9698):1331-8.

4.

Pignata S, Scambia G, Lauria R, et al. A randomized multicenter phase III study comparing

weekly versus every 3 weeks carboplatin (C) plus paclitaxel (P) in patients with advanced

ovarian cancer (AOC): Multicenter italian trials in Ovarian Cancer (MitO-7--European

Network of Gynaecological Oncological trial Groups (ENGOt-ov-10) and Gynecologic

Cancer Intergroup (GCIG) trial. ASCO 2013. Abstract#LBA5501.

5.

Cervantes-Ruiperez A, Hoskins P, Vergote I, et al. Final results of OV16, a phase III

randomized study of sequential cisplatin-topotecan and carboplatin-paclitaxel (CP) versus

CP in first-line chemotherapy for advanced epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC): A GCIG study

of NCIC CTG, EORTC-GCG, and GEICO. ASCO 2013. Abstract#5502.

6.

Hoskins P, Vergote I, Cervantes A, et al. Advanced ovarian cancer: phase III randomized

study of sequential cisplatin-topotecan and carboplatin-paclitaxel vs carboplatin-

paclitaxel. J Natl Cancer Inst 2010;102(20):1547-56.

7.

Friedlander M, Hancock KC, Rischin D, et al. A Phase II, open-label study evaluating

pazopanib in patients with recurrent ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol 2010;119(1):32-7.

8.

Du Bois A, Floquet A, Kim J, et al. Randomized, double-blind, phase III trial of pazopanib

versus placebo in women who have not progressed after first-line chemotherapy for

advanced epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer (AEOC): Results

of an international Intergroup trial (AGO-OVAR16). ASCO 2013. Abstract#LBA5503.

9.

Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Integrated genomic analyses of ovarian

carcinoma. Nature 2011;474(7353):609-15.

10. Degenhardt Y, Lampkin T. Targeting Polo-like kinase in cancer therapy. Clin Cancer Res

2010;16(2):384-9.

11. Rudolph D, Steegmaier M, Hoffmann M, et al. BI 6727, a Polo-like kinase inhibitor

with improved pharmacokinetic profile and broad antitumor activity. Clin Cancer Res

2009;15(9):3094-102.

12. Schöffski P, Awada A, Dumez H, et al. A phase I, dose-escalation study of the novel Polo-

like kinase inhibitor volasertib (BI 6727) in patients with advanced solid tumours. Eur J

Cancer 2012;48(2):179-86.

13. Pujade-Lauraine E, Weber B, Ray-Coquard I, et al. Phase II trial of volasertib (BI 6727)

versus chemotherapy (CT) in platinum-resistant/refractory ovarian cancer (OC). ASCO

2013. Abstract#5505.

14. Bast RC Jr, Hennessy B, Mills GB. The biology of ovarian cancer: new opportunities for

translation. Nat Rev Cancer 2009;9(6):415-28.

15. Press JZ, De Luca A, Boyd N, et al. Ovarian carcinomas with genetic and epigenetic BRCA1

loss have distinct molecular abnormalities. BMC Cancer 2008;8:17. doi: 10.1186/1471-

2407-8-17.

16. Gelmon KA, Tischkowitz M, Mackay H, et al. Olaparib in patients with recurrent high-

grade serous or poorly differentiated ovarian carcinoma or triple-negative breast cancer:

a phase 2, multicentre, open-label, non-randomised study. Lancet Oncol 2011;12(9):852-

61.

17. Ledermann J, Harter P, Gourley C, et al. Olaparib maintenance therapy in platinum-

sensitive relapsed ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med 2012;366(15):1382-92.

18. Ledermann J, Harter P, Gourley C, et al. Olaparib maintenance therapy in patients with

platinum-sensitive relapsed serous ovarian cancer (SOC) and a BRCA mutation (BRCAm).

ASCO 2013. Abstract#5505.

19. Noda K, Ohashi Y, Okada H, et al. Randomized phase II study of immunomodulator

Z-100 in patients with stage IIIB cervical cancer with radiation therapy. Jpn J Clin Oncol

2006;36(9):570-7.

20. Noda K, Ohashi Y, Sugimori H, et al. Phase III double-blind randomized trial of radiation

therapy for stage IIIb cervical cancer in combination with low- or high-dose Z-100:

treatment with immunomodulator, more is not better. Gynecol Oncol 2006;101(3):455-63.

21. Fujiwara K, Ohashi Y, Ochiai K, Noda K. Phase III placebo controlled double blind

randomized trial of radiation therapy for stage 2B-4A cervical cancer with

immunomodulator Z-100: JGOG-DT101 study. ASCO 2013. Abstract#5506.

22. Kantoff PW, Higano CS, Shore ND, et al. Sipuleucel-T immunotherapy for castration-

resistant prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 2010;363(5):411-22.

23. Hogg R, Friedlander M. Biology of epithelial ovarian cancer: implications for screening

women at high genetic risk. J Clin Oncol 2004;22(7):1315-27.

24. Rosenthal AN, Fraser L, Manchanda R, et al. Results of annual screening in phase I of

the United Kingdom familial ovarian cancer screening study highlight the need for strict

adherence to screening schedule. J Clin Oncol 2013;31(1):49-57.

25. Rosenthal A, Fraser L, Philpott S, et al. Final results of 4-monthly screening in the UK

Familial Ovarian Cancer Screening Study (UKFOCSS Phase 2). ASCO 2013. Abstract#5507^.

26. Hampel H, Frankel W, Panescu J, et al. Screening for Lynch syndrome (hereditary

nonpolyposis colorectal cancer) among endometrial cancer patients. Cancer Res

2006;66(15):7810-7.

27. Ferguson S. Screening for Lynch syndrome in unselected women with endometrial cancer.

ASCO 2013. Abstract#5508.

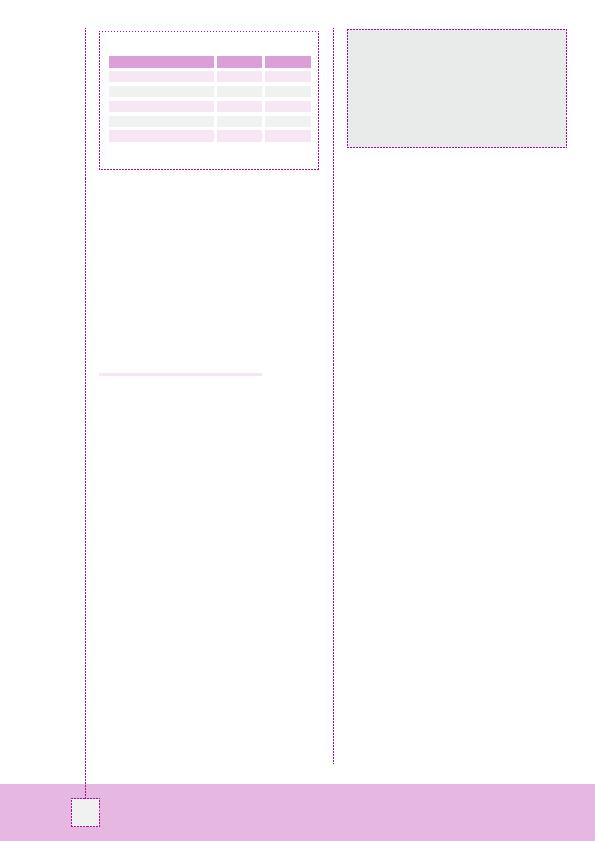

Tableau: Indices de performance du dépistage intensif.

Characteristic

Value (%)

95% CI

Sensitivity (occult true pos.)

100.0

73.5-100

Sensitivity (occult false neg.)

75.0

47.6-92.7

Specificity (occult n/a)

96.1

95.2-97.0

PPV (occult false neg.)

13.0*

6.9-21.7

NPV (occult false neg.)

99.7

99.3-99.9

* Compared with 25% in phase I

«

Ce n'est pas tant le rapprochement des dosages du CA125

que le strict respect du protocole (fût-il annuel) qui a permis la

meilleure réduction du risque. Quant à la conclusion de Sarah

Ferguson, il faut encore la confronter à la réalité économique

en y incluant les conséquences familiales. Et ce calcul semble

positif en faveur de l'immunohistochimie ciblée, au minimum

chez les femmes de moins de 60 ans.»

Michael Friedlander (Sidney)