S A L T U S M A G A Z I N E

2 3

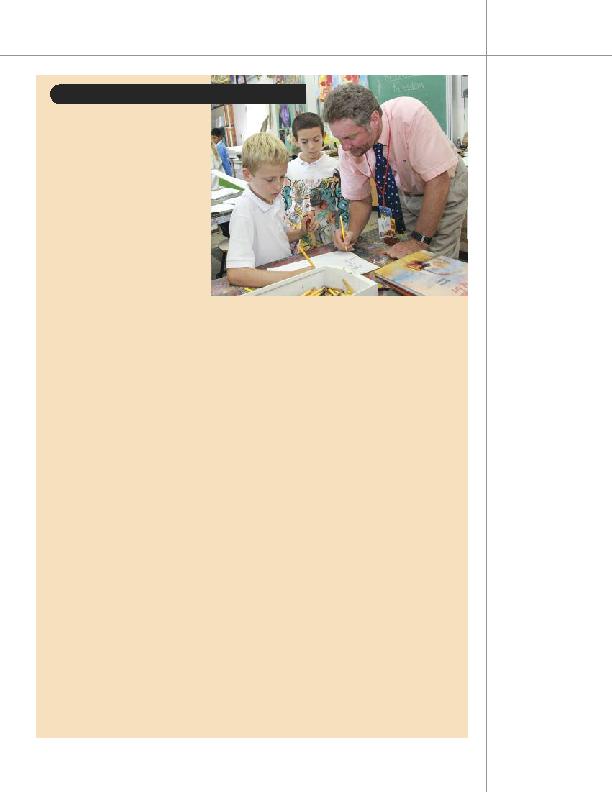

rt teacher Steven Masters's aerie-like classroom

has a piano, rows of stippled tables that look

like Pollack creations, and a potpourri of

eclectic eye candy--from student paintings and giant

palm seedpods to a collection of brass instruments

hanging from the ceiling. It's no wonder the "Northwest

Art Studio," as he's dubbed it, is one of the most

popular corners on campus.

"Visual art is about seeing things differently," says

Mr. Masters, who began his teaching career at Saltus in

1975 and after professional stints as an artist-educator

in both the US and Bermuda, returned to the School

in 2006 to teach Middle School and Upper Primary

students. "I feel it enhances young people's ability to

communicate and it teaches them that there's more

than one way to approach challenges."

The ever-ebullient teacher, whose colourful ties and

ready smile have students buttonholing him whenever

he exits his creative headquarters, believes his art

classes should be exciting for all students--whether

they're on track to become the next Leonardo or not. "I

don't see my job in any way as creating an environment

solely to cater to kids who are going to art school," he

says. "Some of them may--but more importantly, I want

them all to be comfortable with pushing their boundaries,

thinking outside the envelope, being less afraid of new

things, and enjoying the process of making decisions for

themselves. It will help them make judgments about life."

Visual art classes are a mandatory component of

every student's curriculum up to the end of Middle

School through Year 9, after which students elect whether

to continue with art as a GCSE subject and beyond in

Years 10, 11 and SGY1 and 2. Mr. Masters feels no matter

what they choose to pursue at that point, art classes

have helped students approach challenges in all their

subjects. "Perhaps, for instance, they might enhance a

history or geography paper with illustrations," he says.

"It's also about being able to view things from a different

angle, about realising there is more than one way to

conquer a problem, about simplifying stuff and become

the manager of something abstract," he says. "It's a

useful tool for life in general."

Mr. Masters, who also leads two over-subscribed

afterschool clubs--for Upper Primary and Middle

Schoolers--makes his classroom conducive to out-of-

the-box learning. He encourages students to walk

around freely as they work, to listen to music, to

collaborate with him and each other, and to make

suggestions about the task at hand.

"I remember once when I was starting work at

another school," he says. "I walked into a full classroom

and one of the children came running up to me and

pointed at another student. `There's April,' the kid said.

`She's the artist.' I thought how unfortunate that mindset

was--that one student had to suffer the burden of being

the only artist, first of all, and that everyone else felt they

might as well quit and go home!

"I prefer to create an environment where you get a

chance to make mistakes," he says, "to experiment, to

open new avenues to explore, to try something you

haven't tried before, and to find your own means of

expression. It's a process rather than a result I'm after.

That's what art, to me, is all about."

--Rosemary Jones

A

ART

in the

aerie

C

H

A

R

L

E

S

A

N

D

E

R

S

O

N

Steven Masters shows by example in the "Northwest Art Studio"