50

GA

/ Vol. 5 / No.4 / APRIL 2013

I

t's a really good idea that any air-

craft manages to complete a whole

flight without hitting any other

aircraft.

To achieve this: while the airlines

and to some extent the military can

rely upon instrument rules, primary

and secondary radar, and systems

such as TCAS to avoid other traffic,

in reality that's not enough for the

vast majority of VFR traffic, and

even for IFR traffic at lower levels in

VMC. There's always something, or

somebody, which can ruin an aircraft's

day large birds, ultralights, stray

balloons, lost gliders any of these can

appear very quickly, in either controlled

or uncontrolled airspace and lookout

is an essential skill for any pilot.

There are reports out there which

say that see and avoid is largely

ineffective and a waste of time; on the

other hand, certainly my experience

is that during most VFR flights, at

some point, I will see numerous other

aeroplanes, and usually change my

course or height once or twice to

avoid conflicting with other traffic,

and I don't think that I have any

monopoly on good eyes or good

practice. So seeing and avoiding

matters which first means seeing.

But, it's worth asking when

somebody sees another aircraft, or

some birds, or a balloon what do

they actually see? Unless it's very

close, they don't see the colour,

they don't see the shape they see

a contrast. So something large, but

of a similar colour density to the

by Dr Guy Gratton

Aircraft Technical

background, is very hard to spot.

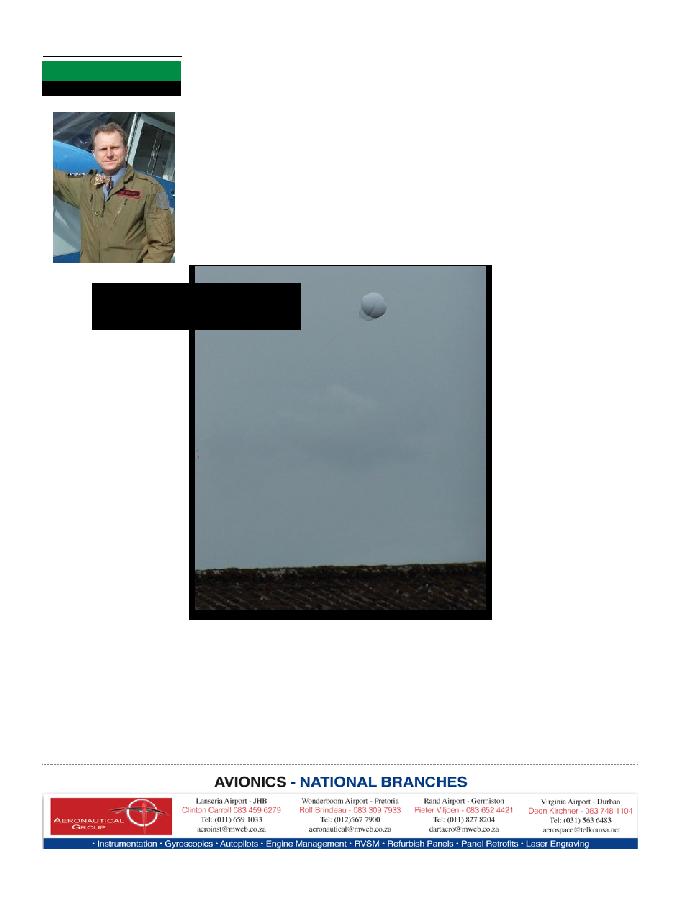

Look at the picture I've shown here of

a sonde balloon it's big, it's close to

the camera, and you'd really struggle

to see it because it's so similar in

colour density to the background.

This is exactly why modern military

aeroplanes are also painted in very

neutral colours throughout this

makes them extremely hard to spot

far harder to spot than the broken

patterns of older military aeroplanes.

So first we can help make

sure that everybody else can see us

by painting our aircraft in colours

that depending upon the main local

backgrounds, are either as light,

or as dark, as possible. Companies

who really think hard about this will

often paint the underside as dark as

possible, and the upper surface as

light as possible particularly with

the colours changing partway up the

side of the fuselage; then, it's pretty

much guaranteed that there will be

a contrast against any background.

Of course, that helps other people

spot you but how do pilots do a

good job of spotting other traffic

whether it's winged, feathered, rotary,

or just floating there? Well looking

straight out of the front window

doesn't help a pilot much unless

they're "lucky" enough that your

traffic is on a perfectly reciprocal

course. Of-course, we have pretty

good peripheral vision as human

beings from about 110 degrees

either side for a young woman,

down to a still good 80ish degrees

either side for a man in his 60s, but

the structure of the eye is such that

peripheral vision is only really good

for picking up motion and if you

want to pick up things that you're

going to hit, motion isn't there. Try a

quick experiment to prove this: hold

a finger up at arm's length to one

side of you, then move your finger

in a straight line to a point a foot or

so in front of your nose. You'll find

that you pick up the finger in your

peripheral vision quite easily, and

as your arm keeps moving, you can

track the movement quite easily.

Now put your finger out at arm's

length again, and move it in directly

towards your nearest eyeball. You

won't see the finger easily until it is

very close, and even then, it will be

really hard to detect the movement.

Now do this a third time, but put your

finger right in front of you and look

at it as you bring it to your face the

shape and movement of your finger

now become very clear although it

is stationary in your field of view.

So, to detect an approaching

finger, sorry: aeroplane, you need to

be looking pretty much at it. And the

same is true for any pilot: if they're

going to spot that conflicting traffic,

they need to be looking at it when

it's close enough to make out the

contrasting shades. So pilots are, or

at-least should be, trained to move

their heads regularly typically six or

eight directions around them, moving

their head to look in that direction

holding the head still, and pausing

to pick up anything that's out there.

(Incidentally, if you've ever met

any fighter pilots, they usually have

necks like rugby forwards. Think

about doing that sort of move with

your head, for most of a flight, whilst

wearing a helmet, and pulling high

g constantly whilst you manoeuvre

and you'll start to realise why.)

So pilots can have a good go at

this but aircraft designers really

don't help as they often make

windows smaller than is ideal, and

also put large pillars between the

windows and doors. Any obstruction

such as a pillar, need to be narrower

than the distance between the pilots'

eyes: if it's the same width or wider,

then there will be gaps behind it.

Unfortunately, most aircraft designers

aren't pilots, and the majority regard

human factors of any sort as an

afterthought, so tend to surround

aeroplane and helicopter cockpits

with blind spots. Thus, the sensible

pilot not only needs to keep turning

his or her head (especially her, as

women's eyes tend to be slightly

closer together), but also need to keep

moving their heads around to ensure

that all these obstructions don't

create any permanent blindspots.

Which is very hard work

moving the head around like that

constantly, perhaps for hours for a

long low level flight, is physically

and mentally demanding. It needs

practice, and for the vast majority of

time of-course, the crew won't see

anything. But any helicopter pilot,

any light aircraft pilot, and any other

pilot or crew member who spends any

significant time in a cockpit, in VMC,

below 10,000ft or so: absolutely

needs that skill and obsession.

And whilst doing all of that

they of-course still need to operate

the aircraft, navigate, co-operate,

and all of the other skills that are

part of the pilots skillset. Not

easy, but always necessary. ·

Seeing to avoid