8

OUR PLANET MAGAZINE

CLIMATE CHANGE AND THE CRYOSPHERE

South America's rivers make available 35 per cent of the world's

surface water resources. Yet snow and ice still represent an important

additional water supply, providing it to mountain valleys and adjacent

arid and semiarid regions. Mountain glaciers in the Andes and the

Patagonia ice shelf supply water for river flow, lakes and reservoirs.

The rivers flowing to the Pacific Ocean have a remarkable seasonal

regime, fed by snow and ice melt in late spring and summer time.

The dry, desert-like Pacific coastal landscape extending from the equator to

central Chile, and the high plateau of Peru and Bolivia, both depend, in large

measure, on snowmelt water.

At the southernmost tip of South America from 29º south, the dry, arid

conditions are on the eastern side of the Andes, south of the rivers Negro

and Colorado. Low precipitation makes its rivers dependent on the melting

of glaciers and of the important ice shelf between 48º south and 52º south.

Although precipitation is higher there, snowmelt also contributes

to the flow of northern Patagonia's rivers. The economically wealthy

regions of Cuyo, in central western Argentina, and central Chile -- home to

large urban populations and important agriculture, fruit growing (mainly

vineyards), hydroelectricity and industry -- also fundamentally depend on

the melting of snow and ice. Indeed the ancient inhabitant of the region, the

Huarpes, called it Cuyum, meaning `Hell's Desert'. Human activity there only

became feasible when European migrants introduced irrigation, starting the

region's development.

The more advanced pre-Colombian civilizations of the Andean inter-

tropical region, managed their water resources remarkably successfully.

The most developed pre-Inca cultures both complemented reduced and

sporadic rainfall water and improved supplies through wise engineering

works, such as by the measured distribution of irrigation water and by

connecting the Atlantic and Pacific watersheds -- building a 74 kilometre-

long channel for water transfer some 3,000 metres up in Cumbemayo.

Climate change is already beginning to have a critical effect on

the living conditions of Andes indigenous communities, on water

dependent human activities, and on natural ecosystems. The availability

of meltwater will increasingly diminish, damaging sustainable development.

Recent studies show that the Peruvian glaciers may disappear altogether

in the coming decades.

The rapid retreat of the inter-tropical Andean glaciers brings further dangers

to local people, and particularly to the indigenous communities of the

high plateaus of Bolivia, Ecuador and Peru, from avalanches and glacier

lake outburst floods. Peru's 19 glaciated mountain ranges contain more

than a half the world's tropical glaciers, mostly in the Cordillera Blanca.

This danger is much less great further south, in the Patagonian Andes, where

the retreat is taking much longer; though the shrinking of the glaciers is still

important there, it does not bring similar hazards and risks.

The best possible use of the resources and potential energy in the large

amount of water still enclosed in the southernmost glaciers would be

to enable the relocation of productive systems to the more than a half

million square kilometres of the semiarid Patagonian plateau. This would

call for conserving the valuable biological diversity of the region and

developing appropriate technology, and for the wise and rational use of

the large quantities of both surface and underground water resulting from

the glaciers' retreat. It can draw on the experience of the agro-industrial

use of the upper basin of the Rio Negro, which, starting in the 1930s,

made possible its transformation to the remarkable exporter of fruit and

wines that it is today. Grain crops, which will suffer decreases in yields in

Argentina's northern agricultural fields, could be relocated, with planned

adaptation, to the Rio Negro's lower basin and to irrigated lands in other

Patagonian sub-regions. The Institute for the Development of the Lower

Basin of the Rio Negro is already developing the necessary feasibility studies.

The energy for such an undertaking may be provided by local hydroelectric

plants and by the steady westerly winds, already under initial exploitation.

El Niño events will bring important snow mass to the Andes below 29º south.

So there must be planned use of meltwater, a selection of plant species better

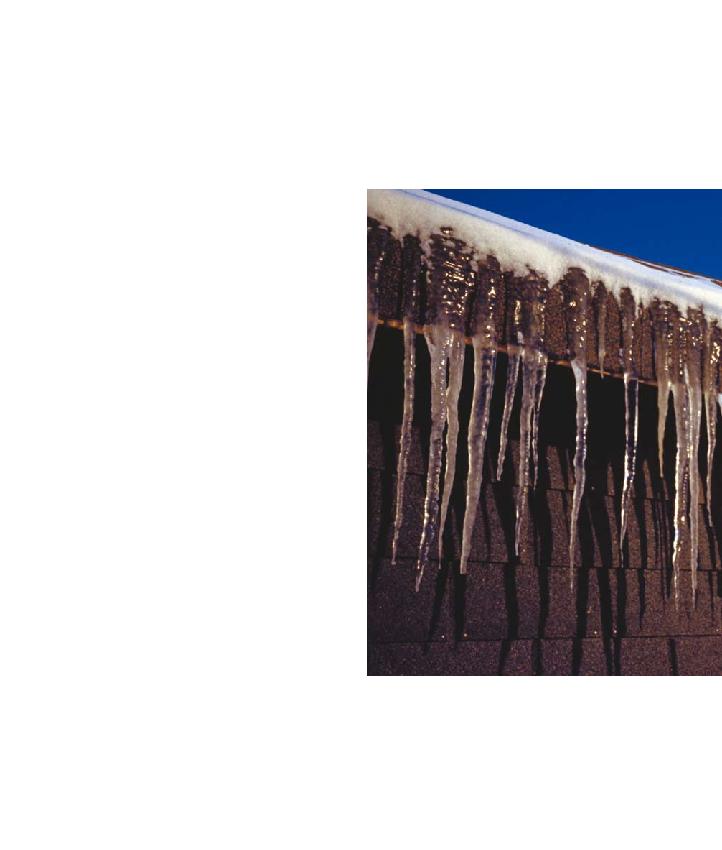

snow, ice and life