A POTENTIAL BIOMARKER

Dr. Burns’ second area of interest is the vascular structure of the retina. When they’re healthy, vascular structures in the eye respond to changes in light by increasing blood flow and by changing their sizes. But Dr. Burns suspects these responses to be compromised by hypertension and diabetes, some of the leading causes of vision loss. With adaptive optics imaging, Dr. Burns can now look at precise, real-time video of the vascular arteries, capillaries, and veins—and actually see the density and growth of blood vessels, the realtime flow of blood, and the thickness of cell walls. The imaging provides the potential to help researchers and clinicians make great strides in diagnosing and monitoring these kinds of diseases. For example, people with diabetes don’t know when to expect complications. But monitoring changes in the vasculature of the retina may identify the onset of problems. “Diagnosis for diabetes usually comes from testing blood sugar, feeling crummy, obesity, things like that,” he says. “A lot of people aren’t diagnosed when they should be, particularly in poorer populations. So there’s a big problem on the detection, but right now adaptive optics is too expensive for screening populations. However, monitoring progression can be even harder. If we can start using these relatively noninvasive tests to be able to appropriately increase the frequency of patient visits for those who need it, and decrease it for those who don’t, that can create savings on both ends,” Dr. Burns says. “I think a lot of medicine is going to go this way, toward more individualized care. It has to.” The new information also shows the potential for the eye to be a biomarker for diseases like diabetes and hypertension. “We can start thinking of the vasculature as a possible biomarker for diseases that go well beyond the health of the eye, into the health of the whole body,” Dr. Burns says. And if the eye could be a disease biomarker, how many diseases might the eye mark? It’s too soon to tell, he says. Regardless, adaptive optics imaging may be enormously beneficial for early damage detection and monitoring compared to more invasive, risky methods currently available, such as kidney and brain biopsies.

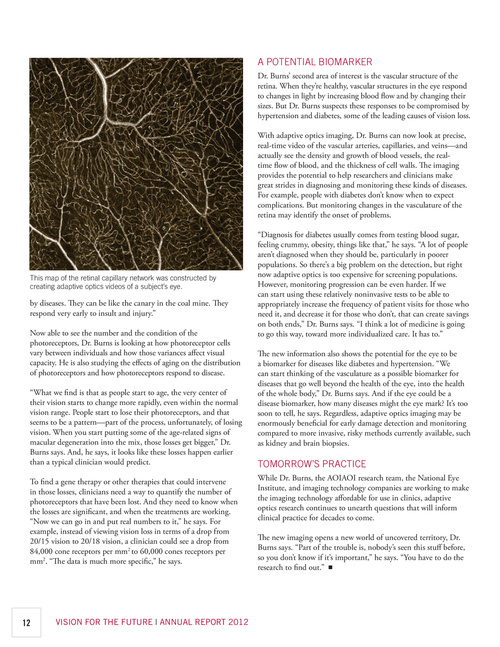

This map of the retinal capillary network was constructed by creating adaptive optics videos of a subject’s eye.

by diseases. They can be like the canary in the coal mine. They respond very early to insult and injury.” Now able to see the number and the condition of the photoreceptors, Dr. Burns is looking at how photoreceptor cells vary between individuals and how those variances affect visual capacity. He is also studying the effects of aging on the distribution of photoreceptors and how photoreceptors respond to disease. “What we find is that as people start to age, the very center of their vision starts to change more rapidly, even within the normal vision range. People start to lose their photoreceptors, and that seems to be a pattern—part of the process, unfortunately, of losing vision. When you start putting some of the age-related signs of macular degeneration into the mix, those losses get bigger,” Dr. Burns says. And, he says, it looks like these losses happen earlier than a typical clinician would predict. To find a gene therapy or other therapies that could intervene in those losses, clinicians need a way to quantify the number of photoreceptors that have been lost. And they need to know when the losses are significant, and when the treatments are working. “Now we can go in and put real numbers to it,” he says. For example, instead of viewing vision loss in terms of a drop from 20/15 vision to 20/18 vision, a clinician could see a drop from 84,000 cone receptors per mm2 to 60,000 cones receptors per mm2. “The data is much more specific,” he says.

TOMORROW’S PRACTICE

While Dr. Burns, the AOIAOI research team, the National Eye Institute, and imaging technology companies are working to make the imaging technology affordable for use in clinics, adaptive optics research continues to unearth questions that will inform clinical practice for decades to come. The new imaging opens a new world of uncovered territory, Dr. Burns says. “Part of the trouble is, nobody’s seen this stuff before, so you don’t know if it’s important,” he says. “You have to do the research to find out.” n

12

VISION FOR THE FUTURE | ANNUAL REPORT 2012